Yesterday marked a year since my husband was diagnosed with a brain tumor, one of the not good kind. I think that I’ve written here a few times since then, I believe, reflecting on some of the changes that have happened. The year and-a-half of the pandemic was marked by loss for us, as it has been for so many, with deaths of friends and family, some expected, some not, some from long-standing illness, one from Covid. The brain tumor was one more surprise of this year. I’ve been using Caring Bridge, mostly, to update friends and family of what’s happening every month regarding his treatment and state of being. So far, he does well.

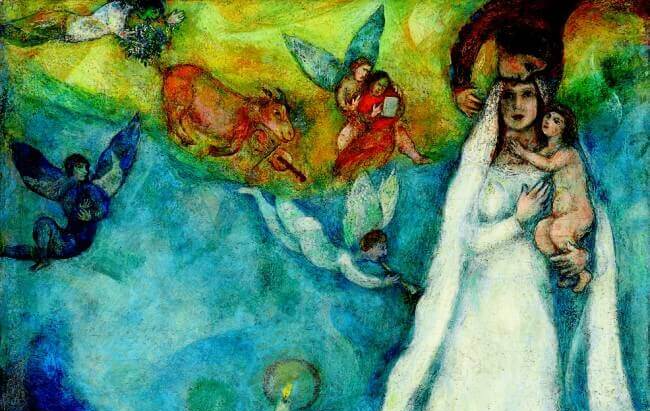

I’m finding my way every day with whatever presents itself. We are living so close to the minutiae of daily life, in part, because attending to the care of someone living with a brain tumor requires that–attention to the minutiae: what will be the challenge of the day, how is the fatigue, is there enough protein in the house, can we go for a walk, or what music will wake up the brain, what healing things can we do. It’s not that we speak of these out loud every day, though some days we do. The many considerations are under the surface all the time. Every day, there are things and events that move us to tears, whether it’s in the immediacy of our personal life–like a grandchild’s sudden smile–or in the public sphere, the ongoing pandemic, the threats to democracy, the suffering of so many people and creatures, the losses of habitats, the droughts, fires, floods, storms. But next to that, next to those tears, is beauty–so jarring to live with both, the suffering and the beauty, every day, and to learn each day to expand the edges of compassion, to keep my seat and bear witness, to act, if I can, in ways of weaving justice, which is very limited right now, and to keep loving.

I went from a very public life as a pastor and community religious leader to a very hidden life. There’s relief and loss in that. Relief for being able to put down some responsibilities, and loss for being able to put down some of those same responsibilities. I miss my public life and our lively community, and I cherish this new very familial and private one.

In this hidden life, courage and perseverance have become the loving virtues that shine most brightly to me, mostly my spouse’s immense courage and devotion to living the fullness of existence. And in the wider world, the courage and perseverance of so many people working to create a better world, who never give up the work of hope and justice. On the small scale, our home scale, the virtues are the same. Why do I rise in this morning? How will I live this day, how will I love, how will I serve?

Today in our hidden life, my beloved went out early in the dawn to pick wild blueberries. It’s a beautiful morning, very mild, post tropical storm Elsa. Picking blueberries is not an easy thing for him. His balance is uncertain on uneven ground, so he has to find a way to set his feet on the granite and moss without feeling like he might fall over. His right hand hand isn’t working very well, from the tumor, so sorting through leaves and picking the berries off takes great concentration. “I dropped quite a few” he reports when he comes in, “good for the birds.” While he was picking, the catbirds talked from the birch tree, and a chickadee dropped into the bushes to feed on the berries, just a foot away from his gentle hands.

Later, we made oatmeal, and ate the berries. I haven’t presided at a communion service since March 15, 2020, when we closed our building. And in October, I left my call to be able to be here at home. But these blueberries, this oatmeal, this beautiful morning, these loving hands that picked the blueberries, the birds in the birch trees, the wet ground, the drift of cloud, my spouse lifting his spoon carefully, this moment, this, too, a communion.

You must be logged in to post a comment.